Subscribe

Subscribe- Login

-

/

Sign Up

- US Black Engineer

- >>

- News

- >>

- How Dr. Donald Wilson Met a Challenge

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Diversity initiatives have increased at U.S. medical schools to address the underrepresentation of minority faculty, but according to a report published by The Journal of the American Medical Association, the percentage of underrepresented minority faculty increased only modestly from 6.8 percent in 2000 to 8.0 percent in 2010.

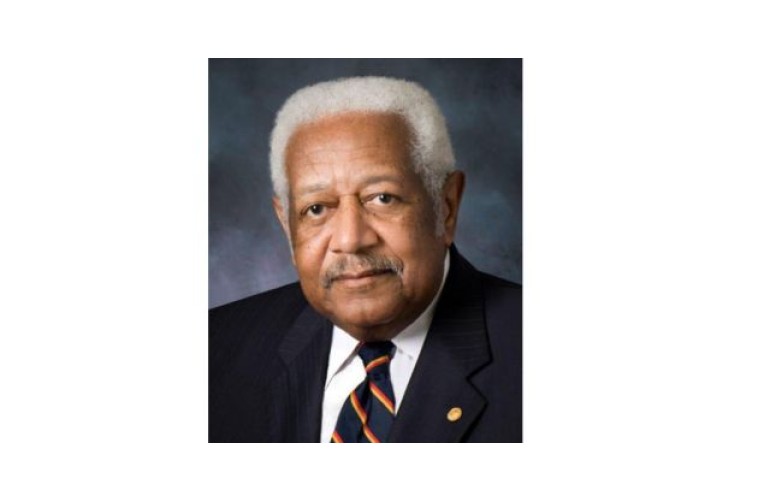

USBE magazine recently spoke to Dr. Donald E. Wilson, professor and Dean Emeritus at the University of Maryland School, who’s been doing a lot about the lack of diversity in academic medicine in his role as an active participant at teaching hospitals and minority development programs.

“One of the problems with diversity is the underrepresentation of minorities in investigative medicine,” Dr. Wilson explained.

“The National Institutes of Health (NIH) made this award to an organization I’ve been part of for many years and am one of the founders–the Association for Academic Minority Physicians, Inc. (AAMP),” he said. “The objective is to expand success rates and get more people into the professions. We pre-preview ideas and offer critical insight on research proposals for grant applications.”

According to the AAMP’s website, the organization works to increase the number of people currently underrepresented in biomedical research, academic medicine and ultimately health care delivery and leadership.

The AAMP membership offers advice and mentorship to students, trainees, and junior faculty. AAMP also sponsors an annual scientific meeting especially designed to allow young investigators to present their research in a supportive environment.

My Greatest Challenge

Dr. Wilson’s many accomplishments include serving as the first Black chairman of the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) and the AAMC Council of Deans.

As dean at the University of Maryland School of Medicine (1991 to 2006), he was the first African American to serve at a non-minority medical school in the United States. But Dr. Wilson almost didn’t get the job in 1991 and this is his story.

“About 1988/9 the University of Maryland was searching for a dean of the medical school. They contacted me and asked if I could apply, I said I would. So I came and interviewed and I never heard from them again,” Wilson said.

Six months later Wilson asked a colleague ‘what about that dean’s job at the medical school?’ and he was told the talent search had been called off.

He was shocked to know the university hadn’t gotten back to him after the interview.

A year went by and one member of the faculty in the same medical school called Dr. Wilson to tell him they were looking for a dean.

“I’m not interested,” he recalled replying. “I dealt with them once and they didn’t have the courtesy to get back.”

Navigating the cultural climate

After some convincing, Wilson agreed to re-apply, but he never heard back. A couple of months later, he ran into the faculty member who had talked him into giving the process another go.

Wilson admits the selection process was one his greatest challenges and he would have withdrawn but for the support from friendly faculty in Baltimore.

Asked to describe his leadership style, he wrapped it up in one word: Persistence.

Wilson surely needed quite a lot of that. Because when he finally got on campus, he found out that eleven department chairs out of the twenty or so in post thought they should have the job of dean of the medical school.

“I had to bring people along,” Wilson said on winning buy-in.

Even in the face of an infamous plot to remove him, hatched rather boisterously at a downtown restaurant in full hearing of diners–one of whom just happened to be the dean of another medical school who promptly informed Wilson the next day.

Getting things done took “an enormous amount of work,” Wilson said. “It wasn’t a job for the faint-hearted,” he added.

4 Things Dr. Wilson got done

As dean of the University of Maryland School of Medicine, he:

1. Increased annual grant and contract awards from $77 million to $350 million.

2. Grew annual philanthropic support for the School of Medicine from $1.7 million to $37M.

3. Quadrupled the number of full-time underrepresented faculty at the School of Medicine, significantly increased the number of women faculty and created one of the most diverse student bodies and faculties in the country.

4. Required all first-year medical students to do informatics, the science of information and computer information systems

Born in Worcester, Massachusetts in 1936, Wilson says his inspiration comes from his parents who between them had little more than a sixth-grade education. They worked hard to pay his way through Harvard, where he was one of only seven Black males in a class of 1,072 students, and later medical school.

Although Wilson’s mother passed away before he graduated from college, he went on to receive his M.D. from Tufts University in 1962. Wilson’s father would watch his son rise in academic medicine. Wilson remembers fondly how his father would often ask when he planned on becoming a “real doctor.”

Last April, he received the American College of Physicians’ 2015 W. Lester Henry Award. Established 2008, in honor of Dr. W. Lester Henry, the first Black regent and master of the college, the award is given to an American College of Physician (ACP) member with accomplishments in advancing diversity in clinical medicine/research, and/or access to care relating to economically disadvantaged patient populations, minorities, immigrant groups, or the homeless; and groups underrepresented in the healthcare workforce.

What others say about him

In a 2006 tribute, when Wilson was retiring as dean of the University of Maryland School of Medicine and as vice president of medical affairs for the University of Maryland, Sen. Ben Cardin, said he had “transformed the landscape of American medicine and medical education at the University of Maryland.”

Under his leadership, construction of biomedical research buildings strengthened the school’s capacity as it tackled such health issues as HIV/AIDS and schizophrenia.

Additionally, Dr. Wilson guided the school through curriculum reform, generating greater awareness of problem-based learning and better integration of basic and clinical education. His commitment to the education of minority students in the field of medicine led him to found the Association of Academic Minority Physicians.

“Dr. Wilson has been a good and trusted adviser to me on health care policy,” Cardin said. “He has spoken out about the need to expand research into diseases that are more prevalent in the African-American community and among women. His service on the Maryland Health Care Commission has helped to guarantee access to emergency health care for all Marylanders while ensuring that hospitals are able to provide those services,” Cardin said.

Best Advice

“If I look at something and I think I can make it better, I will,” Wilson said. “If I think I can’t, I leave it alone. I’m not interested in banging my head against a brick wall.”

Wilson recalls how he worked to improve confidence during his tenure. When a young University of Maryland researcher declined to put in a proposal because he felt a much larger academic rival would win it anyway, and that funders couldn’t possibly award two grants in the same town, Wilson gave the staffer 48 hours to produce the grant application. The University of Maryland won the grant.

After 15 years as dean and vice president at Maryland and a full year of retirement, Wilson went back to work as senior vice president for health sciences at Howard University from 2007-2009 before retiring again in 2009. Five years earlier, he had had a kidney transplant, followed by a second in 2009.

At Howard, he helped transform its three health science colleges and the historic Howard University Hospital. He has also served as chief of gastroenterology at the University Of Illinois Medical School in Chicago and chairman of medicine at SUNY, Downstate in Brooklyn.

Dr. Wilson has chaired the NIH Digestive Diseases Advisory Committee, the FDA Gastrointestinal Drugs Advisory Committee, and the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (DHHS) Advisory Council. He was also a member of the advisory committee to the director of the NIH. He is a member of the National Academy of Medicine (formerly the Institute of Medicine) of the National Academy of Sciences, the Association of American Physicians, and the American Clinical and Climatological Association. He served as vice president of the Alpha Omega Alpha (AOA) national board of directors from 2004-2011, the National Medical Honors Society, and is a Master of the American College of Physicians.

“It was a good run,” Wilson said.”You’ve got to examine your need about wanting to do it,” he advised on career progression. “If it’s just to build your own career, then forget about it,” he said.

“If you’re ready to do things so other people can advance, if you’re ready to do things for an institution to improve, then I think you’re ready,” he said.